Presidential Pardons and Reprieves: The Conscience of the Nation – By Daniel Sheridan

Presidential Pardons and Reprieves: The Conscience of the Nation – By Daniel Sheridan

There was a political T.V. show that aired in the early 2000s called, “The West Wing.” Actor Martin Sheen plays President Bartlett. One of the episodes dealt with the matter of pardons. As President Bartlett is contemplating pardons he says to his Chief of Staff Leo McGarry:

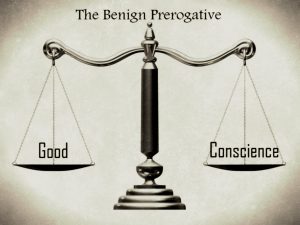

“The benign prerogative, that’s what Hamilton called them.”

McGarry replies: “Benign? It’s a bag of lit dynamite.”

That’s both funny and true. There’s always controversy when a President offers Pardons or Reprieves. Usually at the end of an administration tempers flare over the President’s use of this power. At the end of a recent administration the President used his pardoning power in a popular case, a move which inspired many partisan responses. Some praised the President saying,

“It’s about time!” “Justice is finally served.” “This is a good sign.”

Others lashed out in anger,

“He’s a traitor!” “Only a few more days and he’s gone.” “A travesty of justice.”

Sentiments like that are why the fictional Leo McGarry called this prerogative a “bag of lit dynamite.”

A good friend of mine expressed her frustration over this issue in a Facebook post:

“I never understood the reason that the president has the right to pardon or lessen the time served by criminals. Somebody please explain why this makes any sense. How can a judge who hears the entire case, a jury who convicts a criminal, and a law that is in place for penalty be overturned by somebody a week before their term ends? I really don’t get it.”

She’s frustrated. But she’s also asking questions. That’s where we need to start, asking the right questions. What is this Constitutional power all about? That’s where I want to offer my services. I’m not going to offer opinions on specific cases which certain Presidents have acted on. What I will do is explain what I understand to be the original intent of this Presidential power. First we must have a common understanding of the Constitutional provision as originally intended. Then, after acquiring such knowledge, it’s up to each individual citizen to make up his or her mind, after considering all the facts, regarding his or her opinion of a President’s action in a particular case. It’s ok if citizens disagree regarding a President’s pardon or reprieve of so-and so; but let’s at least agree on what the Presidential power is about. Plus, I think if we understand the historical circumstances which led to this Constitutional provision, our hearts will soften, we’ll tone down the viciousness of our criticisms, and it might even bring us closer together as a people.

Here we go.

First, the power is granted to the President to grant pardons and reprieves for Federal crimes alone. The Constitution reads,

“The President shall…have power to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.”

Reprieves are usually granted when new evidence or testimony is brought to light that was unknown during the defendant’s trial, information which could have affected the outcome. The President can grant a reprieve so this new evidence can be examined.

The pardon is a little different. It’s not about declaring a person innocent; it’s about the nature of the sentence in relation to the crime. The sentence might have been too harsh; the punishment didn’t fit the crime. Maybe there are certain circumstances that should be taken into consideration in relation to the crime.

The pardoning power is referred to as “the conscience of the nation.” The President, when offering reprieves or pardons, is acting in mercy on behalf of the American people when a true sense of justice calls for intervention.

The Constitutional clause wasn’t intended to weaken the sense of the rule of law; it actually strengthens it by avoiding the extremes of harsh and cruel punishments. The clause demonstrates that we are far from perfect knowledge in matters of justice. It requires that we learn from our mistakes and correct them. This provision is a confession that our laws aren’t perfect, they therefore at times need to be revised, unlike the laws of the ancient Medes and Persians which couldn’t be altered. Alexander Hamilton says this,

“Humanity and good policy conspire to dictate, that the benign prerogative of pardoning should be as little as possible fettered or embarrassed. The criminal code of every country partakes so much of necessary severity, that without an easy access to exceptions in favor of unfortunate guilt, justice would wear a countenance too sanguinary and cruel…” (Federalist #84)

In other words, criminal codes throughout history have been too harsh, therefore the pardon and reprieve powers are meant to eliminate cruelty and promote true justice. The Founders were acknowledging that even in their own day some of their judicial practices were barbaric and the people needed protection from them! What an honest confession!

This Constitutional provision also applies to cases where the accused suffers injustice because he or she didn’t have access to competent legal help. Incompetent or corrupt lawyers may merit the accused the Benign Prerogative.

It also applies to cases where an unpopular defendant has been convicted in the court of public opinion before the trial even begins. The public sentiment influences the outcome of the trial and the facts of the case are overruled by blind hatred. One of the sad features of human nature is that people will condemn a person they don’t like regardless of the facts and evidence. Personal animosity, which bends facts to its will, is enthroned as the highest law from which there is no appeal, facts and evidence are derided. The Benign Prerogative intervenes in such cases after tempers are cooled thus sparing the nation from making shipwreck of conscience.

The opposite of this can happen too. If the accused is popular, his or her fans will overlook or even justify the crimes of their hero. In either case, justice isn’t served.

James Iredell of North Carolina said,

“Another power that he has is to grant pardons, except in cases of impeachment. I believe it is the sense of a great part of America, that this power should be exercised by their governors…It is the genius of a republican government that the laws should be rigidly executed, without the influence of favor or ill-will–that, when a man commits a crime, however powerful he or his friends may be, yet he should be punished for it; and, on the other hand, though he should be universally hated by his country, his real guilt alone, as to the particular charge, is to operate against him. This strict and scrupulous observance of justice is proper in all governments; but it is particularly indispensable in a republican one, because, in such a government, the law is superior to every man, and no man is superior to another. But, though this general principle be unquestionable, surely there is no gentleman…who is not aware that there ought to be exceptions to it; because there may be many instances where, though a man offends against the letter of the law, yet peculiar circumstances in his case may entitle him to mercy…This power, however, only refers to offences against the United States, and not against particular states.”

That’s the “Benign Prerogative,” my fellow Americans. Mercy and truth meet together. It’s the “Conscience of the Nation,” which is based on mercy, humanity, even justice, and good policy.

Aren’t you proud that this beautiful principle is in our U.S. Constitution? The U.S. Constitution. Read it. Know it. Share it. Get your Pocket Constitutions at www.FreedomFactor.org.

The Voting Rights Act – By Daniel W. Sheridan (Twitter: @DanielWSheridan)

The Voting Rights Act – By Daniel W. Sheridan (Twitter: @DanielWSheridan)